My experience with

Awake Brain Surgery

“During an awake craniotomy for resecting part of her astrocytoma, a patient-investigator faces a high-stakes decision that she will make in collaboration with her neurosurgeon.”

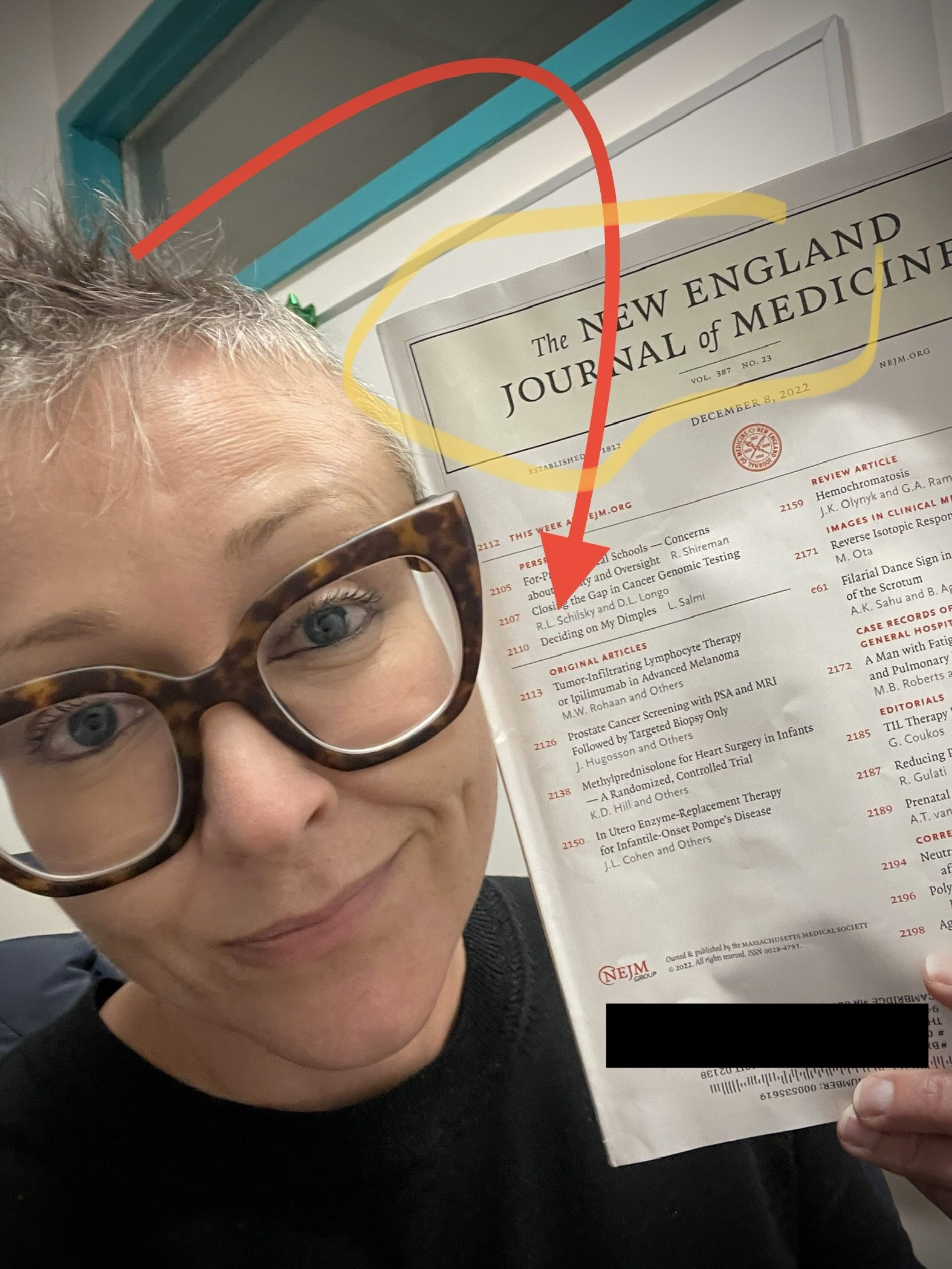

From Deciding on My Dimples, Liz Salmi, AS, 387(23), 2110–2111. Copyright © 2022 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission.

Deciding on My Dimples

Salmi, L. (2022). Deciding on my dimples. New England Journal of Medicine, 387(23), 2110–2111. doi: 10.1056/nejmp2210418. AUTHOR COPY.

This article, shared by the author, is for educational use, and follows the Author Permissions guidelines at NEJM.org.

“OK, boss, it’s time for us to make a few decisions,” my neurosurgeon, Shawn Hervey-Jumper, announced. He was removing a malignant tumor from my brain, and we were nearing the end of the procedure. It wasn’t my first craniotomy — it was my fourth — but this time the stakes were much higher. As someone who has been living with a grade 2 astrocytoma for 15 years, I’ve long since accepted reality. Though initially indolent, these tumors commonly progress to a more aggressive grade.

As the director of the Glial Tumor Neuroscience Program at the University of California, San Francisco, Shawn specializes in removing tumors from within functional regions of the brain using brain-mapping techniques. He has dedicated his life to understanding how the brain maintains and recovers language, sensory, motor, and cognitive abilities. For my part, I’m not only a patient, but also a patient advocate and scholar, part of a burgeoning movement in which patients are becoming patient-investigators. Open, transparent communication between clinicians and patients is a key focus of my work, and this moment captured something essential about my nontraditional journey toward academic medicine.

“I’ve removed as much tumor as I can see,” Shawn explained. “Based on what you’re telling me, Liz, we’re in your face. If I go any farther in this area, I’m putting you at an increased risk of sensory and motor loss due to the tumor’s proximity to the motor cortex. How do you want to proceed?”

Shawn and I had discussed contingencies in advance. We knew there would be sensory loss, although we didn’t know exactly where. We’d explored the real possibility that I would eventually develop weaknesses, ranging in severity from foot drop to complete inability to move my right leg. Shared decision making can be uncomfortable for all involved. More than talking about my overall prognosis, discussing mobility deficits made me cry . . . and made him go silent.

As much as Shawn and I had prepared for such possibilities, and though I have learned more about my own neuroanatomy with each passing surgery, the imminent prospect of sensory, and especially motor, loss in my face came as a shock. Time stopped as I gamed out the possible ramifications: Will I be unhappy with my appearance? Would these dimples I inherited from my father never be seen again?

Throughout my life, people have complimented me on my dimples — a defining feature. My husband jokes that I have a “resting smiley face,” and by giving the impression that I’m always smiling, my dimples may have indirectly shaped my persona. I’ve learned that a kind and smiling face is welcome in nearly any setting. Moreover, my dimples have additional meaning for me: I’m pretty sure my father’s genes can take credit for them. But might he have given me a brain tumor gene as well? Most neuro-oncologists will tell you that no familial links exist in glioma, yet 7 years ago my father had a seizure and then a scan: “Bifrontal tumor mass suggestive of glioblastoma.” I still have a photo I took of our MRIs side by side. Our scans are our last father–daughter portrait.

If my tumor becomes more aggressive months from now, will I regret this decision about my face? Why doesn’t my surgeon just give me the answers to this question? I had seconds to weigh the pros and cons. One thing I know for sure: No patient is more engaged than one partnering with a neurosurgeon during awake craniotomy.

Throughout the operation, Shawn was positioned to access my parietal lobe. We both wore headset microphones and could communicate easily. I lay on my side. He monitored my physical and sensory responses while I continuously moved my right leg and arm. Sampling my tumor intermittently while monitoring and mapping my nervous system, Shawn continued to remove pieces of the mass from my brain. Only when tissue was sent to the neuropathologist would he pause. The report that came back after each real-time examination helped him decide whether to keep resecting.

I tried to encode in my memory every interaction in the operating room. The future of my treatment and quality of life hinged on successful resection and accurate pathology reports. In addition, a portion of the resected tissue would be sent to a lab for a study of recurrent low-grade glioma for which I’m a coinvestigator. Fortunately, Shawn understood the multiple layers of complexity and factored them into our communications. As he mapped and resected, I provided continuous feedback about my function and strength, and Shawn shared updates with me. It felt like we were playing an epic game of telephone.

“They’re telling me we’re still finding grade 2 astrocytoma,” he said. “Let’s get more tissue and send it back to the lab, OK?”

Since I’ve had my glioma for more than a decade, my brain has reorganized, and some of the functional areas have shifted over time. I’d heard of neuroplasticity but never considered how long-term survivors of brain tumors, like me, might benefit from such transformation. Shawn and I hypothesize that such adaptation is part of the reason why I maintained my ability to move, even as a substantial portion of my tumor was removed.

“Where do you feel this?” Using a cortical stimulator, Shawn probed areas along the sensory strip, and I’d answer with the corresponding location: Toe. Arch of foot. Ankle. Calf. Shin. Knee. Hip. Hand. Elbow. Shoulder. As phantom sensations worked their way along my right side, I felt privileged in a strange sort of way. Shawn dedicates his life to this work — does he ever wonder what it’s like to feel things from my point of view?

“You’re in my neck.” Maybe I was imagining things, but Shawn’s voice appeared to rise and intensify as he moved the stimulator to new areas. “Now you’re on my cheek.” I felt a tingle on my face and reflexively smiled.

“I think . . . you’re in my dimple.” Shawn stopped.

“OK, boss, it’s time for you to decide,” he said. “If I go any farther, I’m putting you at an increased risk of sensory and motor loss in your face. How do you want to proceed?”

Much of what Shawn and I had discussed in advance had prepared me for this moment. I thought again about my quality of life and how it could change as a result of sensory and motor loss. Vanity made me wonder if every day I’d regret seeing a new reflection in the mirror. I knew my tumor was acting more aggressively than it had previously. I thought about my dad, his dimples, and his death from glioblastoma.

“Let’s stop here,” I decided.

“Are you sure?”

“I’m sure.”

Shawn signaled to the surgical team that my part of the work was over. Physically and emotionally exhausted, I felt relieved as they released me to sleep. Later, awakening with bleary eyes in the neurological intensive care unit, I asked the nursing staff why my muscles were sore. I felt like I’d run a marathon.

That same night, wearing nonslip socks, I paced the floor with a walker. Forty-eight hours later, I was discharged, walking on my own two feet. Six weeks to the day after surgery, Shawn cleared me to return to regular activity. Except that I can’t drive yet — I’ve returned to running, but it will take time for my leg to grasp the spatial difference between a gas pedal and a brake pedal.

In the days and weeks after surgery, my doctors received final pathology reports and results from a genomic panel. Amazingly, after 15 years, my diagnosis remains grade 2 astrocytoma. But the tumor is growing, and I’ve started radiation, to be followed by treatment with temozolomide.

With surgery in our rearview mirrors, the decisions we shared are behind us, and our paths a surgeon and patient now diverge. But my curiosity is piqued, and I suspect my next research collaboration will be inspired by my time in the operating room. Once you’ve traveled to the moon, the Earth never looks the same again.

Deciding on My Dimples

Liz Salmi, A.S.

DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp2210418

AUTHOR COPY available for download as a PDF.

Disclosure forms provided by the author are available at NEJM.org. From Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston. This article was published on December 3, 2022, at NEJM.org. Copyright © 2022 Massachusetts Medical Society.

KEYWORDS: brain tumor, patient experience, brain surgery, neurosurgery, informed consent, quality of life, doctor-patient communication, treatment decision-making, shared decision-making surgical expectations, awake brain surgery, intraoperative mapping, neurosurgery, brain tumors, language mapping, motor mapping, awake craniotomy, preoperative evaluation, brain mapping techniques, surgical planning, awake brain mapping, tumor resection